Roasting Green

Drivers on Interstate 81, north of Syracuse, can smell the coffee. The source? The Paul deLima Coffee roasting plant, a company that is reducing its carbon footprint -- and its costs -- with renewable energy.

The plant is inconspicuous, except for its windmill and solar panels, which seem as out of place in the area as the coffee production itself.

The coffee company, owned and operated by the Drescher family, is using renewable energy to lower its energy costs and reduce its carbon footprint. About 10 years ago, Warner Energy, Paul deLima’s sister company, saw an emerging opportunity in renewable energy, and used the coffee producer’s roasting and distribution facilities as a testing ground for wind and solar power.

The wind turbine and solar photovoltaic array were installed and commissioned in 2009, connecting directly to the electric grid. Together, they have provided much of the energy used by the roaster and the adjoining store ever since: about 14 megawatt hours annually from the turbine, and 8.8 megawatt hours annually from the solar photovoltaic array.

Recently, however, the company’s costs have gone up, with the installation of a new roaster and grinder to increase production. Mike Drescher, a son of one of the owners, said it was time to increase their energy efficiency, updating the solar panels to capitalize on advances in the technology since they were installed. The goal is to once again have most of the company’s energy needs met by renewable sources.

At Paul deLima, the smell of coffee pulls visitors into the store, where they are warmly greeted by Kate Drescher, Mike’s sister, or Glenn Guy, Mike’s uncle, and invited to have a cup of coffee.

The store sells Paul deLima ground coffee and beans (ground on request) from a variety of countries and in a variety of blends. DeLima branded products, such as coffee mugs, are also available for purchase.

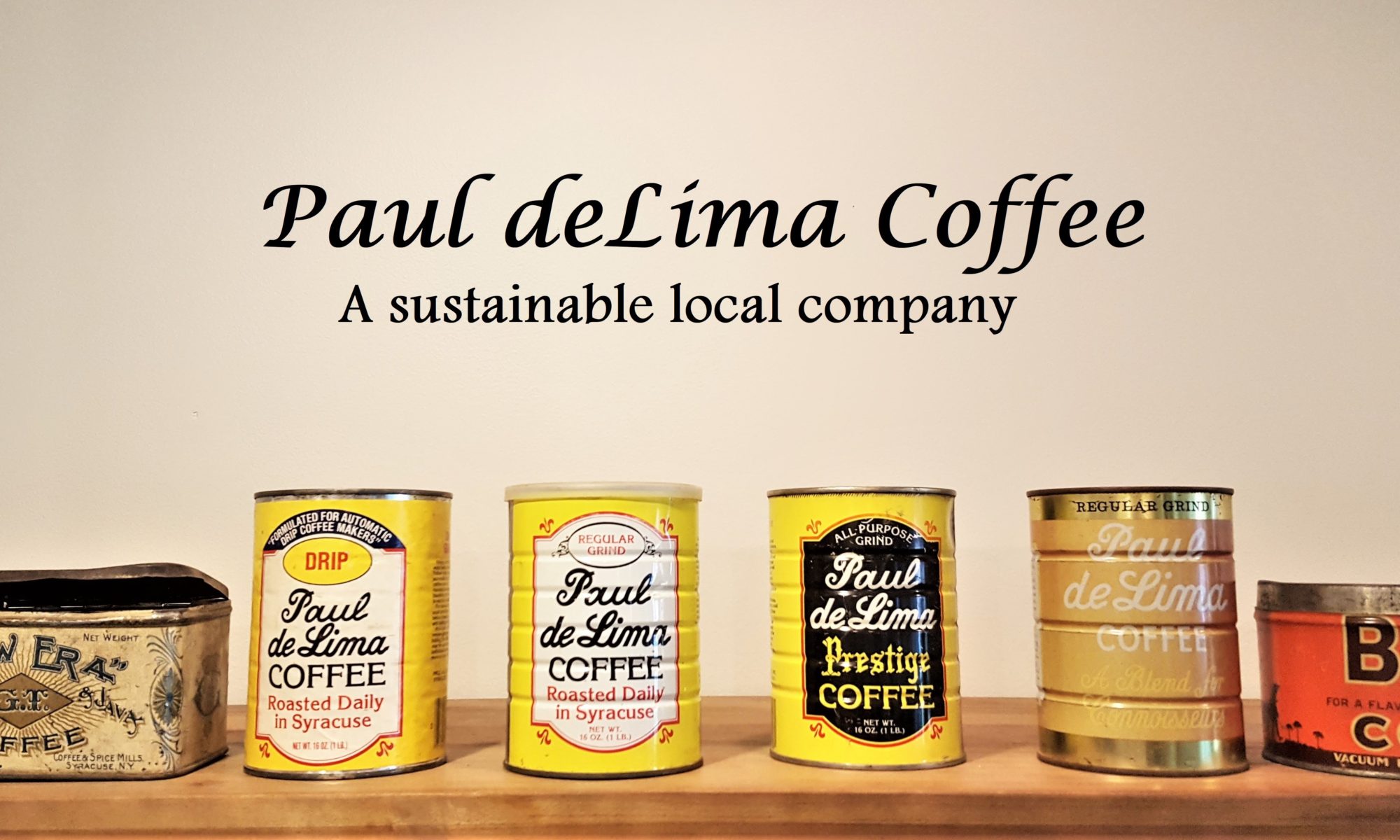

Above the merchandise are displays of old coffee cans, mostly from the early years of the company. The odds-on favorite of the staff is a circa 1960s can that still has the key attached to the bottom and is filled with coffee. Despite its novelty, the staff members say the coffee is probably best left in the container at this point, but they are curious how it tastes.

Adjacent to the store is a hallway with photos highlighting the development of the company by the deLima family from the early 20th century. The story begins with Ella Barber deLima, who traveled to Syracuse in 1902 and began roasting beans from her husband’s family farm in Brazil. The beans were so popular with friends that she started a small business in her kitchen. The company was incorporated by her son in 1916.

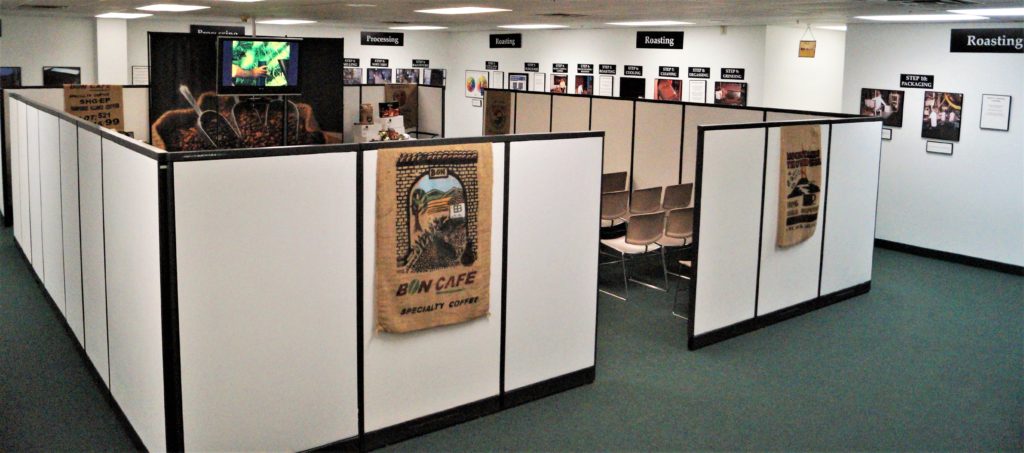

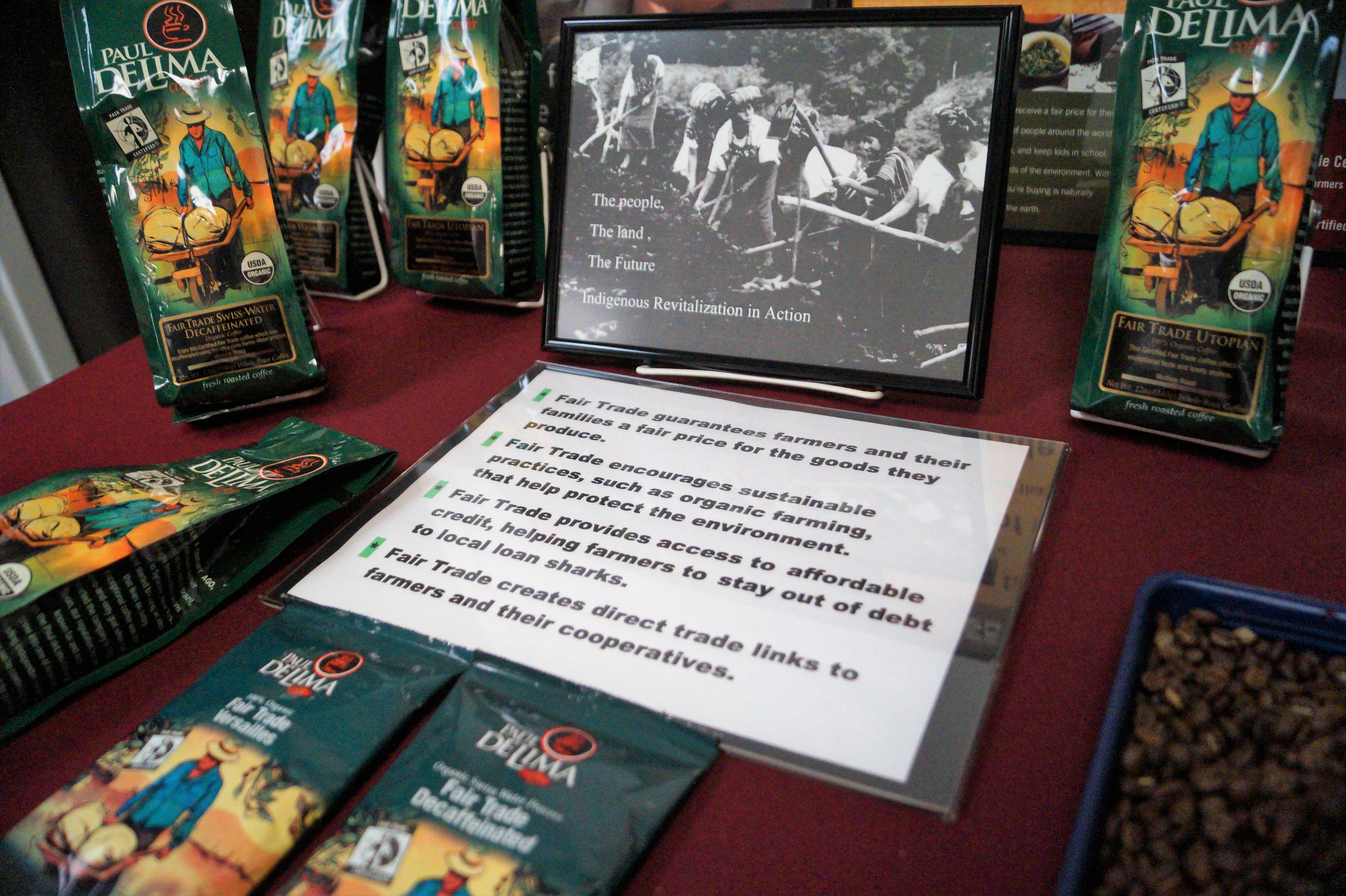

At the end of the hallway is a museum with exhibits about the process of growing and making coffee. In one area, visitors can run their fingers through green or roasted coffee beans, read about fair trade practices (which Paul deLima participates in), and check out old equipment.

The newer equipment is in the roastery at the heart of the facility, where workers don hairnets and beard nets while leaving items behind that might fall into the coffee, like rings and necklaces. Mike Drescher will occasionally lead visitors on a prearranged tour, no cameras allowed, where the aroma of coffee permeates everything. In the roasting area, they arrange burlap sacks full of fresh coffee beans, pour the beans into the sorter to remove stones, and then send them through the roaster and grinder, before placing them in large sacks for transportation to the company’s packaging and distribution center.

In the roastery, they use or recycle nearly everything. There is even a special dumpster for burlap sacks, where people or businesses can take them for free. Many of the sacks are currently going to a farmer, who shreds them to be used for mulching. This focus on sustainability and reducing waste has reduced their carbon dioxide emissions, while saving the company money on waste disposal, Mike Drescher said. He added that the other way the company keeps costs down is by co-manufacturing coffee for other companies. Sometimes those companies even send over beans they want roasted, and the extra business is significant enough to keep production profitable for Paul deLima.

The experienced tasters at the plant – known as “cuppers” – agree that the best room in Paul deLima is the cupping room. The cupping process involves roasting the beans, grinding them, soaking them in hot water, breaking the crust, and removing the “creme,” a white film that forms on the surface after the crust sinks to the bottom. All of this is done in prescribed amounts and for specific lengths of time.

Then each cupper takes quick sips of concentrated coffee made from beans grown in various coffee-producing countries. If the beans aren’t up to their standards, the cuppers won’t order from that batch, or they will return the shipment if the beans were already ordered.

This vetting process keeps the quality of the coffee that Paul deLima sells high, Mike Drescher said, and saves loads that have already been ordered from being returned. In 20 years, he said, they have only returned one shipment to the source, a testament to the advantage of testing the batches prior to ordering.

Glenn Guy explained that for the purposes of testing, the coffee is made stronger than normal in order for the different notes to be more noticeable. Much like wine and beer tasting, each cupper will identify different flavors, and they each have to learn his or her own taste profile for good beans from different regions.

The cuppers spend many weeks in training, learning the taste of beans from one region before moving to beans from another region. Along the way, they are tested and must correctly identify the beans or go through more training. After a cupping session, all the cuppers discuss the beans and decide if any of them tasted “off” in some way, meaning they should not be ordered.

Kate Drescher, Mike Drescher, Glenn Guy, Ryan Cummings, and Ron Chrysler all take part in the cupping process, and if visitors are lucky they can witness the daily ritual through a large window in the store.

The new roaster, low transportation of wastes, and the renewable energy sources all decrease the carbon footprint of Paul deLima coffee. Mike said that the company orders beans from all coffee-producing countries, which are located in tropical regions that are at increased risk for impacts from climate change. As global temperatures rise, these areas may no longer be suitable for growing coffee as a crop. Simply moving north will not solve the problem, Mike Drescher said, because temperature is not the only factor: the levels of precipitation that coffee plants need to grow are changing as well. By reducing their emissions, they are helping to mitigate the impacts of climate change, and contributing to sustainability in the tropical regions where the beans are grown.

He said he thinks it will be a challenge to find new regions to grow coffee in a changing climate, while meeting world demand.

“What’s going to happen? I don’t know,” he says, “but I’m curious.”